If you’ve ever heard that someone took LSD and jumped out a window believing they could fly, you’re not alone. It’s one of the most persistent cautionary tales about psychedelics — repeated in health classes, anti-drug campaigns, and late-night conversations for decades.

The problem? The story doesn’t really hold up. It’s a mash-up of tragedy, rumour, and fear-driven storytelling that took on a life of its own.

At its centre was a family in shock. A father searching for meaning in his daughter’s death found an explanation that the world was eager to accept. That single moment of grief and false certainty reshaped how an entire generation understood LSD — and turned his daughter into a symbol she never chose to be.

The Tragedy That Became a Cautionary Tale

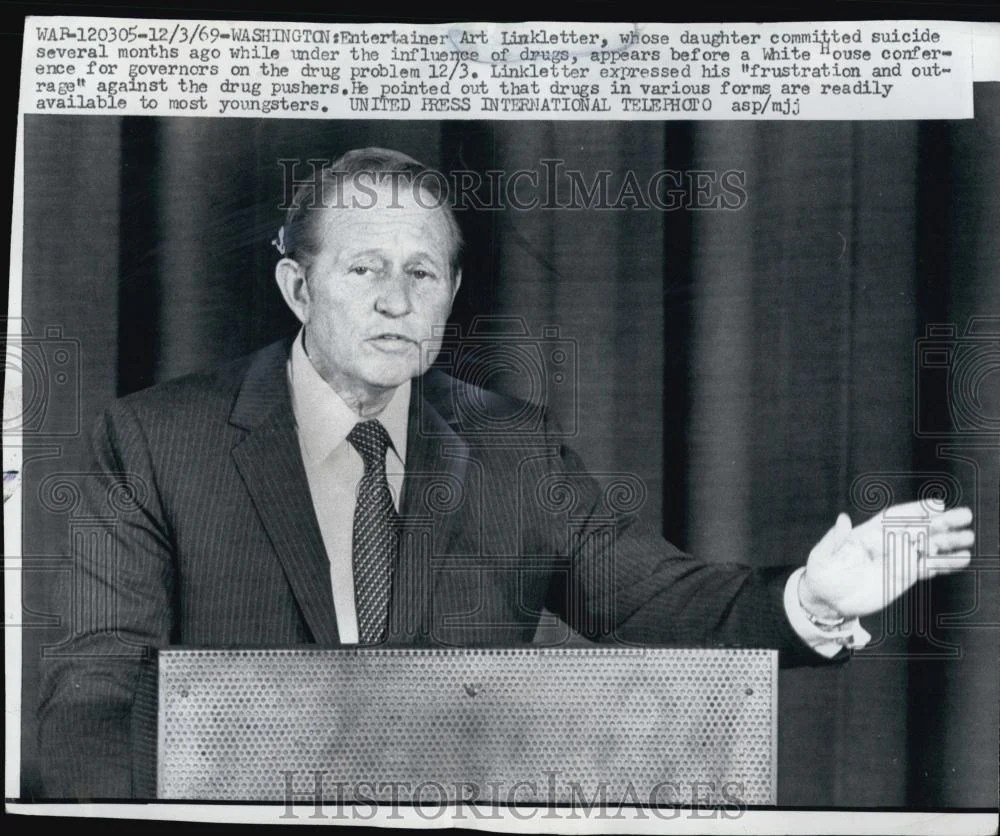

In October 1969, twenty-year-old Diane Linkletter fell from her sixth-floor apartment window in Los Angeles and died. She was the daughter of television host Art Linkletter, America’s genial father figure, whose wholesome shows had defined mid-century comfort and order.

Within hours of her death, Art faced the press. He said LSD was responsible — that Diane had taken the drug months earlier and suffered a “flashback” that drove her to jump. The story fit perfectly into a growing national panic over psychedelics, and it spread instantly.

But when the coroner’s report came back, it told a quieter story. Toxicology found no LSD in her system. Police found no evidence she had taken it recently. Friends described emotional struggles and sleeplessness, not hallucinations.

Still, the truth couldn’t compete with the narrative. In the public imagination, a bright young woman had taken acid and believed she could fly. The tragedy became a warning, and LSD became the villain.

For anyone who’s lost a child, that reaction makes painful sense. Grief demands a reason. When the real reasons are messy, invisible, or beyond comprehension, the mind grabs hold of whatever offers structure. As a parent who has lived through that same kind of loss, I understand Art’s impulse. You look for something you can fight — because the alternative is unbearable.

It doesn’t make him wrong, only human. But his certainty, amplified by his fame, transformed a private heartbreak into a public myth that would shape the story of psychedelics for decades.

How the Story Spread

Once Diane’s story hit the headlines, it took on a life of its own.

The details blurred — sometimes it was a college student, sometimes a nameless girl, always someone who took LSD and jumped. It became a kind of modern folktale, retold in classrooms and whispered by parents who wanted to keep their kids safe.

Years later, another “LSD window death” came to light, though it had happened long before Diane’s. In 1953, Frank Olson, a U.S. Army scientist, was secretly given LSD by the CIA without his consent as part of the MKUltra program. Nine days later, he fell from a New York hotel window. His death was ruled a suicide, though much remains uncertain.

Unlike Diane, Olson wasn’t a recreational user; he was an unwitting subject in a covert government experiment. His story stayed classified for more than twenty years, emerging only in the 1970s — after Diane’s tragedy had already burned the “acid jump” image into the public mind. When Olson’s case finally surfaced, it reinforced what people already believed: LSD could make you lose your mind and leap to your death.

Two very different stories, decades apart, merged into a single myth — and in neither case did the person actually have LSD in their system at the time of death.

What the Evidence Shows

Modern research tells a far less sensational story. LSD is not physiologically toxic, and deaths directly caused by it are extraordinarily rare.

A 2024 Australian review of LSD- and psilocybin-related deaths found that nearly all involved accidents or other substances, not overdose or psychosis.

And when it comes to overall harm, LSD ranks dramatically lower than many legal substances.

According to a comprehensive study published in The Lancet (2010) and reaffirmed by follow-up analyses in 2023, researchers scored drugs on combined harm to users and society:

Substance Overall Harm Score (to user + others)

| Alcohol | 72 |

| Heroin | 55 |

| Crack cocaine | 54 |

| Methamphetamine | 33 |

| Tobacco | 26 |

| Cannabis | 20 |

| LSD | 7 |

| Psilocybin mushrooms | 6 |

These numbers reflect LSD’s low toxicity, low addiction potential, and minimal social harm. It doesn’t make people violent, damage organs, or cause fatal overdoses. When harm does occur, it’s almost always due to context — mixing substances like alcohol or cannabis, being in unsafe environments, or entering the experience in a fragile mental state.

In short: LSD’s reputation as a danger to life and sanity was built more on fear than fact. Ironically, modern research now shows that LSD and other psychedelics can enhance brain connectivity, emotional processing, openness, and overall well-being in guided, therapeutic contexts — the very qualities that could help heal the pain once blamed on them.

Remembering the Real Diane

Diane Linkletter was not a morality tale. She was a young woman navigating a complicated era, and her death reflected pain that can’t be simplified to a slogan.

Her father’s grief was real, but his explanation — amplified by a fearful culture — changed the trajectory of public understanding. From there, a wave of political and moral panic followed, one that would eventually shutter decades of legitimate psychedelic research.

Sometimes I think about the irony. Art Linkletter’s reaction, born of pain, helped fuel a decades-long war that silenced psychedelic research — research that might have changed how we treat mental illness. Since learning what these medicines can do, I’ve wondered if they could have helped Alexander, or even just changed how I understood his pain. Maybe, in a different world, he’d still be here.

I can already feel my next post forming in my head — one that looks more closely at how fear became policy, and how science was silenced for decades because of it.

For now, the truth is simpler:

No one ever jumped out of a window believing they could fly on LSD. What it did was reveal how deeply we need stories to make sense of loss — even when those stories take flight on borrowed wings.

Sources & Further Reading

- “Diane Linkletter” – Wikipedia

- NDARC Fact Sheet: LSD (2025)

- A retrospective study of LSD- and psilocybin-related deaths in Australia (2024)

- Healthline: Can You Overdose on LSD?

- The Guardian: From Mind Control to Murder – Frank Olson and the CIA

- Nutt et al., Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis, The Lancet (2010)

Next in this series: how fear, politics, and moral panic shut down psychedelic research for fifty years — and what’s finally changing.

Leave a comment